They say that the July 4th weekend is a good time to take a break from the news and check out the Major League Baseball standings. Based on today’s records, it looks like the Rangers and the Cubs will play each other in the 2016 World Series.

It is also a weekend to remember the greatest pitching duel of the last 60 years. In fact, they even wrote a book about it: The Greatest Game Ever Pitched: Juan Marichal, Warren Spahn and the Pitching Duel of the Century!

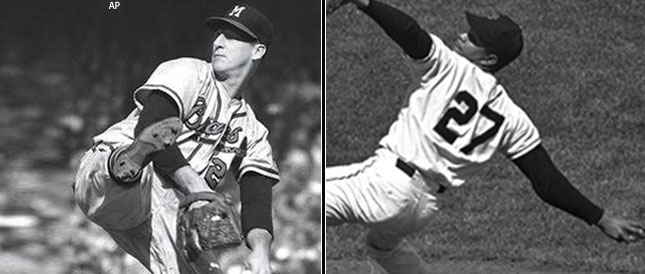

Let’s take a quick look at the two pitchers.

Warren Spahn was an established veteran by the time this game started in San Francisco. He came to Milwaukee with the Boston Braves in 1953. He won 363 games, a 3.09 ERA and completed 382, or more than he won!

Juan Marichal was 25 and establishing himself. He would go on to win 244 games with 2.89 career ERA, and he also completed more games (244) than he won.

I should add that future Hall of Famers Willie Mays, Orlando Cepeda, Willie McCovey, Hank Aaron, and Eddie Matthews took the field that night. Add Marichal and Spahn, and the game featured seven of the greatest players of recent history.

My guess is that most fans expected another low-scoring night game at Candlestick Park. However, they got thegreatest pitching duel in modern baseball history:

At slightly past eight o’clock, Marichal took the Candlestick Park mound.Four hours and 15 innings later, he was still toiling there.And so was Warren Spahn–in a scoreless pitching duel.The Braves had mounted a serious scoring threat in the top of the fourth inning. Marichal disposed of the first two batters before trouble arose.The right-hander walked Norm Larker, and Mack “The Knife” Jones followed with a single to left, moving Larker to second.Del Crandall hit a soft single to center that Willie Mays caught, then lasered to the plate to nail Larker trying to score. It had been a charmed half-inning for the Dominican pitcher.Henry Aaron led off the frame with a drive to deep left field that Marichal said, the next day, he thought was gone. Willie McCovey hauled the ball in a few feet from the fence, as Candlestick Point’s strong westerly winds knocked it down.McCovey nearly ended the game in the bottom of the ninth. The Giants’ left fielder smoked a pitch deep to right field, just missing a home run–or so said the first base umpire. Local beat writer Curly Grieve expanded: “McCovey was so enraged when Chris Pelekoudas called the blast a foul that momentarily it appeared he would push the arbiter around the outfield and wind up ejected in the clubhouse. McCovey, [manager] Alvin Dark and [first base coach] Larry Jansen surrounded Pelekoudas, claiming the ball left Candlestick fair. Pelekoudas stuck to his call, which took courage.”“I followed the ball all the way out but evidently the umpire didn’t. It was at least three feet fair when it left the park. I think the umpire was watching where it landed and made his call on that. As hard as I hit the ball it didn’t have a chance to curve before leaving the ball park,” McCovey said after the game.3 When he stepped back into the batter’s box, a miffed McCovey grounded out to first base, with Spahn covering. After a two-out single by Felipe Alou, Orlando Cepeda popped up to third base, and the scoreless game moved into extra innings.With two outs in the top of the 13th, Braves’ second baseman Frank Bolling singled off Marichal, ending a string of 16 batters in a row retired by the Giants’ workhorse since a walk to Aaron in the eighth. Bolling was left stranded by the next hitter, Aaron, who popped up to first baseman Cepeda in foul ground.Marichal was scheduled to bat third that inning. Cepeda later recalled the moment in a 1998 memoir. Manager Alvin Dark asked Marichal if he had had enough. Cepeda remembered Marichal barking at Dark, “A 42-year-old man is still pitching. I can’t come out!” Dark accepted — or was startled into acceptance by Marichal’s ardor — and let him bat. Marichal flied out to complete the inning, and the game pushed forward.The Giants made a strong bid to get Marichal a win in the lower half of the 14th. With two outs, they loaded the bases on a double, walk and error by Denis Menke, in at third base for Eddie Mathews. But Spahn then coolly retired Giants’ catcher Ed Bailey on a fly to center, ending the inning and extending the deadlock.Marichal went back out for the 15th time and retired the side in order. Likewise, Spahn put the Giants down cleanly in the bottom of the frame. The pitchers had recorded 90 outs through 15 innings of gritty pitching, neither yielding a run.In the 16th, Marichal allowed a two-out single to Menke, and then registered his 48th out of the night on Larker’s comebacker to the mound. It was Marichal’s 227th pitch.When the Giants hit, Spahn retired Harvey Kuenn on a fly out. That brought up future Hall of Famer Mays, still hitless on the long night. Now, Mays drove Spahn’s first pitch through the teeth of the wind in left. The ball cleared the fence, and with that, a masterfully-pitched game dramatically ended. Marichal was the exhausted victor; Spahn, the valiantly defeated.“I’ve been around a long time and that’s the finest exhibition of throwing I’ve ever seen,” Henry Aaron assessed. “It may be 10 years or even 20 before you see another its equal.”Only once, in the more than half-century since, has one pitcher thrown as many innings in one major league baseball game as Marichal did that night against Spahn.After the game, Spahn’s teammates greeted their aged warrior–the last player to enter their clubhouse because of an interview session–with their own tribute.Quoting Spahn’s fellow starting pitcher Bob Sadowski, writer Jim Kaplan described it: “When Spahn arrived, everyone stood, applauded, and lined up to shake his hand. ‘If you didn’t have tears in your eyes, you weren’t nothing,'”Over the 16 innings, Marichal allowed eight hits and four walks and struck out 10. Spahn, who threw 201 pitches of his own, yielded nine hits, walked only one (intentionally), and fanned a pair. Both men made their next scheduled starts five days later, the Sunday before the All-Star Game. Spahn complained of a sore elbow, which apparently flared up enough to cause him to miss two starts later in the month, but he pitched through it to lead the 1963 National League with 22 complete games.

Today, we call it a quality start when a guy goes six innings. We count pitches and start talking about it around 100.

Years ago, Marichal and Spahn battled each other until Mays ended the game with a homer. They didn’t quit; they just kept going and going.

It was more than a pitching duel. It was a demonstration of character and work ethic. We could use a bit of that these days.

P.S. You can listen to my show. If you like our posts, please look for ”Donate” on the right column of the blog page.